Week 11’s driving question was how can a clinical decision support system (CDSS) improve the quality of healthcare? Specifically, the task was to think of a clinical scenario and suggest a CDSS that can be imbedded in Community Health Information Tracking System (CHITS), an electronic medical record system crafted by the University of the Philippines Manila National Telehealth Center (UPM-NTHC), now being used in some government regional health units.

www.americanehr.com

CDSS espouses evidence-based medicine, envisioned to reduce practice variation and improve quality of care. CDSS provides both the physician a (or health care professional) and the patient with computer-generated knowledge, at the point of care. It should be able to provide reminders and warnings, to both the one providing care, and the one seeking care; and pertinent to my hypothetical case, generate a list of patients eligible for a specific intervention (as for example, immunisation).

This hypothetical case is that of Jacob, a 10-year old boy who consults the regional health unit for fever and colds. When his chart was pulled up by the nurse, his immunisation record showed that while he received his BCG, DPT, OPV and Hepatitis B vaccination (required in the Philippines’ Expanded Program of Immunization), he never received his measles vaccination which should have be given at around 9 months of age.

A good CDSS for this case, should have “flagged” Jacob for having missed his measles vaccination. The system should allow the scheduling of the vaccination, which naturally has to take place after being treated for his colds. This alert should continue until such vaccination is received. The CDSS should allow scheduling of appointments for vaccination, and should also permit entry of the information when the vaccination is finally received.

Ideally, a CDSS that will address measles vaccination and compliance should be able to generate a list of patients in the system eligible for receiving our desired intervention, which is the measles vaccination in this case. When such a list is generated, health care providers, and perhaps in some cases the local government units or social workers, can help track such patients, and make them available for the intervention.

Additionally, CDSS alerts for rubella vaccination can also be used even before conception. Family planning seminars a requisite for getting a marriage license is perfect timing for would-be mothers to receive information and vaccination. The same is true for mothers who consult prenatally at the regional health units. There should be no second child with rubella. Nine months before a child is born, is plenty of opportunity to alert this mother of the need for a rubella vaccine when the situation is ripe for her to receive such a vaccine. In the same manner, mothers who give birth to patients with rubella, should be alerted that all other children not exposed as yet are good candidates for receiving the vaccine.

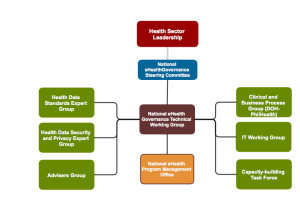

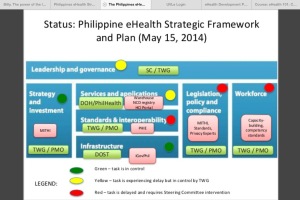

For rubella vaccination to achieve our desired outcome or reduced mortality and morbidity from congenital rubella syndrome, a 95% vaccination coverage is necessary. The Philippines used to reach 70%, and even then we lament. Latest figures put Metro Manila at 40%, we waited for an epidemic before a LIGTAS TIGDAS campaign was launched. While yet unable to achieve targets, a question of sustaining immunisation campaigns should also be addressed. Incorporating alerts, reminders, and trackers in CHITS is one such means to achieve this goal. Is CHITS ready?